In my post, Of Complex Systems and Birds, one of the questions I touched on was why complex systems were difficult for us to decipher. I mentioned that it was mostly because of how our thinking had been shaped over the last few centuries and that I would cover the topic in a separate post. Here it is.

In this post, I explore why most of us don’t think simple and deep enough today, what that means, how our environment shapes our thinking, what kind of impact it has on us individually and collectively, and what we could do about it. It is a deep and wide-ranging topic, and we don’t have all the answers yet. Let me know what you think by leaving a comment. Thank you!

My husband, Bing, is an engineer by training and a natural at all things engineering. He is also the family chef, an amazing one, and a natural at that too. What I mean by natural is that he knows the fundamentals of his craft, so he doesn’t need any instructions to create something.

Bing never looks at recipes. Years ago, we saw a picture of a dish on a magazine cover that looked tasty. A few days later, we had a dish on the dinner table that resembled the one on the magazine cover. We never knew if it tasted the same as the one pictured in the magazine, but it didn’t matter. The dish on our table was delicious and refreshing.

On the other hand, I can only make meals by following recipes, serious ones such as shepherd’s pie, lasagna, paella, and scones. I don’t know how to cook without recipes.

During the Christmas holidays last year, we tried to make gluten-free (GF) bread using our rarely-used three-year-old bread machine. But the GF bread never came out right despite the fact that we measured everything precisely and followed the recipes to a tee. Bing ditched the bread machine and took things into his own hands. He made the GF dough in the good old-fashioned way, covered it in a bowl, and placed it on a heating vent to let it rise. He checked on the dough a few times and started baking when the dough rose just enough. It was the best GF bread we’ve made.

There was something simpler yet deeper and more meaningful about the whole process.

When we understand something deeply, it becomes simple, more meaningful and transparent, almost in a philosophical way. Einstein was right: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”

“Executing Recipes” vs. Understanding

Most of us don’t think simple enough today. In other words, we don’t understand much of what we do in a deep and connected way. We think in a broad-brush way similar to recipe execution.

This is not to say that we need to do everything from scratch organically every time. If we did so, we would be trapped in an analysis-paralysis deep hole and never accomplish anything. The question is to know when to dig deep and when to execute recipes. Problems arise when we should unpack and understand things and make them simple, but we don’t, both individually and collectively.

Recipe execution is remarkably efficient. Throughout human civilization, especially Industrial Revolution, it has fueled economic growth, lifted billions out of poverty, and brought general prosperity to the world. The benefit is undeniable. The trend is continuing.

I recently rebuilt my website by executing a stack of “recipes”. Coming from a technical background, I wasn’t clueless to start with. Here were the general steps I followed:

- I needed a domain name (the address of my website), which I already had, jdstream.ca.

- I needed a platform to construct and maintain the website. WordPress came as a no-brainer. It is a free, open-source, wildly popular website creation platform.

- I needed a hosting service provider (all websites need one). A hosting provider is the “house” where all the content/files of a website live. It is also where the website address points to when someone looks for it. I quickly decided to go with Bluehost, an official WordPress-recommended hosting provider.

- Then it was time to construct the website/house:

- Determining the layout of the website. A quick Google told me that there were over 8,000 free WordPress themes available. A theme provides the overall design of a website similar to the layout of a house. I picked the Astra theme after examining a few.

- I was delighted to discover that Astra offers 23 starter templates. Starter templates are pre-built websites with dummy content so that I didn’t have to deal with the inner workings. How wonderful! I selected a template.

- I installed Astra and the template on my Bluehost server. It was a matter of clicking on a button.

- It was time to customize the general properties of my website. This includes the colour and typography, selecting/designing images, header and footer, menu items, and the number of pages. There are enough options and flexibility for customization in the theme and template to make a website look unique.

- Finally, it was time to build the actual content. By the way, many themes come with plugins with drag-and-drop capabilities for easy construction of the content. There are also plugins for advanced features such as security and analytics.

- I launched my website.

As you can see, I was able to build a functioning, personalized website without much understanding of its inner workings. I relied on the “recipes” from experts in WordPress, Bluehost, Astra, and many others. Most steps were black boxes to me but user-friendly enough to make me feel in control. When I accidentally broke something, I found that my best option and sometimes the only option was to retrieve an earlier version from the server at the expense of losing some content. Although the site is running and functioning fine from what I can see, there are still errors from the Google search console (the GPS for websites) indicating that it may have trouble pointing people to my site. I have no idea why. After spending a couple of days trying to investigate the issue including reaching out to the plugin vendor, a separate business entity from Astra, I gave up for now. Convenience often hides the truth, unfortunately.

Problems With “Executing Recipes”

Today we rely on recipes for almost everything we do without much understanding. We execute recipes for meals, fitness, health, childcare, education, relationships, and work procedures. The list goes on.

We experts are supposed to have a deep understanding of our specialties, and some of us do. But many don’t. What we often do instead is execute stacks of recipes, and we do it with conviction and efficiency. If you are an expert who feels like a cog in a large, complicated machine, you are likely executing recipes most of the time. Besides, there are other serious problems at both the individual level and the collective level.

Every recipe has context, purpose, and scope. When executing recipes, we focus on the steps (doing things right) instead of on the purpose (doing the right things). When executing stacks of recipes, we tend to inadvertently complicate things instead of making things simple. We are also more likely to do the wrong things. Further, when we get stuck, it is difficult for us to untangle and figure out where and how to intervene.

Collectively, we have become a recipe execution society. This renders us incapable of understanding complex issues facing us all individually, organizationally, socially and environmentally. To understand what we can do about it, we need to unpack how our brain works first.

How Does the Brain Work?

The brain is considered the most important organ (although not the only one) that controls our ability to think, feel, see, hear, walk and much more.

We are all born with a half-baked brain. The other half is shaped and live wired through our interactions with the world around us. Our values, beliefs and experiences in both the physical and social environments play a critical role in shaping our brain’s structure and function. As Martin Heidegger posited, “every man is born as many men and dies as a single one.” (David Eagleman, Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain, 2020).

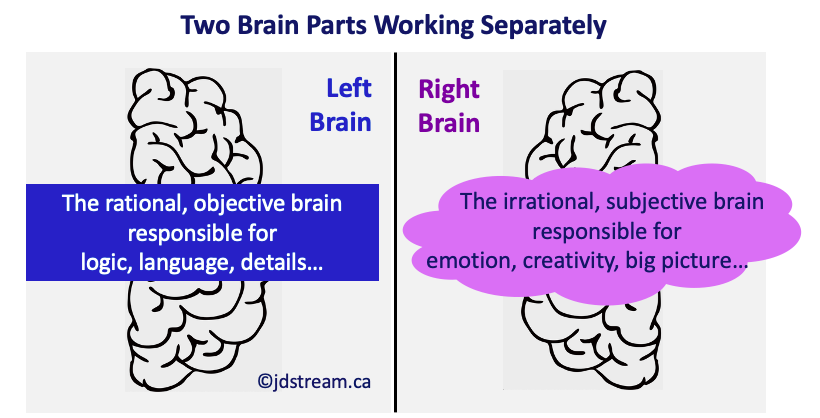

Anatomically and architecturally, our brain has two hemispheres, the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere. We often refer to them as the left brain and the right brain. The common belief is that the two hemispheres are separate entities and operate independently. See the figure below for each brain’s responsibilities.

However, research from recent decades reveals that the brain as a whole is a complex system. It accomplishes its functions through the interactions of the two hemispheres. Psychiatrist Ian McGilchrist published his 20 years of research in The Master and Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (2009).

He argues that although the two brain hemispheres have different responsibilities, they work together instead of separately to perform most of the brain functions. In fact, the right hemisphere is the master, delegating certain tasks to the left hemisphere, the emissary. For example, for language, the right hemisphere comes up with ideas and delegates the left hemisphere to put the ideas into words grammatically and logically. When we hear other people speak, the left hemisphere parses the words and sends them over to the right hemisphere to interpret and make sense of the meaning.

The left hemisphere is responsible for things that are known and predictable, things that require narrow, focused attention, such as doing math. The right hemisphere is responsible for things that are unpredictable and uncertain such as threats or danger. It scans and evaluates its surroundings and keeps its eyes open for multiple options and possibilities.

Simply put, the left hemisphere analyzes the details of the parts (“recipe execution”), and the right hemisphere synthesizes the information from the left hemisphere and makes sense of the whole. Therefore, understanding comes from the interactions of both hemispheres.

It is also true for the brains of birds and other animals. When a bird tries to pick up a seed, it needs to focus rather narrowly and sharply, and it does so with its left hemisphere while its right hemisphere stays alert for predators and other things. Without the two hemispheres working together simultaneously, birds and other animals would not survive long.

When the two brain hemispheres are in balance, we function more harmoniously with nature.

How Has Industrialization Shaped Our Thinking?

Over the course of industrialization, our two brain hemispheres became out of balance as we increasingly valued and therefore practiced things that the left hemisphere is responsible for. After all, who wouldn’t value rational, logical, analytical reasoning over irrational, subjective, intuitive ones? Or so we thought.

We believed that if we could take things apart and analyze the parts, we would understand the whole and the universe. After more than 500 years of taking things apart, science just started to recognize that atoms, electrons and quarks alone can’t answer questions such as how ecosystems evolve, how birds migrate, how languages develop, how an economy grows, how traffic flows, how social systems emerge, and how intelligence arises in all living systems. There is much more out there than what our left brain alone can parse.

Although rational, logical reasoning is sound in itself, the big problem is when we overuse it to the exclusion of all other ways of thinking and forms of knowing, and when we ignore the things that we couldn’t reason logically and rationally (yet).

Thinking in parts, aka analytical thinking, has become our dominant, default mode of thinking. As a result, we have reduced our perceptions to one-dimensional. We become trapped in the details of the parts, unable to understand the meaning of the things we do and make sense of the world around us. As McGilchrist puts it: “We have the knowledge of the parts in spades but have lost the wisdom of the whole.”

Even when we recognize that there are multiple intertwining factors in an issue, we tend to establish linear causal connections and narrow them down to one factor that we can control. It is why complex systems are so difficult for our lopsided, analytical, linear brain to decipher.

How to think has become a lost art in the hustle and bustle of modern life complicated by stacks of “recipes” to be executed.

Complexity Thinking – An Antidote to “Recipe Execution”

A new field, complexity science or the science of complex systems, sprang up to explain and navigate the real world we live in, random, unpredictable, and beyond our control. Complexity thinking is about thinking in collective wholes as opposed to thinking in individual parts.

We are good at understanding individuals or parts. We are terrible at understanding collectives or complex wholes. Throughout human history, narratives, including biblical stories, are usually about individual heroes, leaders, and explorers, and are rarely about collectives. So, we don’t have human collective role models to follow. The systems we built, physical or social, tend to depend on individual heroes and leaders. (For more on individuals vs. collectives, stay tuned for my upcoming post, “More is Different”.)

About a month after this post was published, a connection of mine, Becky Andree, shared a LinkedIn post with a beautiful addition about complexity thinking. I had to update this blog post to include it. Here is what she said: “complexity of thinking is actually both thinking in the collective and thinking in the parts. Our capacity to complexly think is a continuum and dependent on the domain that we are interacting with. As our complexity of thinking develops, we shift from thinking in discrete parts, seeing the relationship, then seeing the paradox and the whole. Within different domains, we might be at different parts of the continuum. Our motivation and interests often determine what parts of the continuum we reach.” Thank you! Becky.

A popular near-synonym for complexity thinking is systems thinking. Yasmin Merali and Peter Allen’s paper from 2011, Complexity and Systems Thinking, describes the evolution of systems thinking through its various stages of development over the millennia from a management science perspective. It covers cybernetics, general systems theory, systems engineering, complexity science and everything in between. Melanie Mitchell’s book, Complexity: A Guided Tour (2010) has detailed and comprehensive coverage of complex systems research and key figures who contributed to its development.

Although I use both terms interchangeably, I prefer using complexity thinking as it deals with systems that do not have causality relationships.

Finally, how can we practice complexity thinking?

Unfortunately, there are no recipes for practicing complexity thinking. A good starting point is to read as much as you can about complex systems. If you would like to unpack the science of complex systems, Santa Fe Institute offers a wealth of information and online courses (some are free) to explore. If you are interested in general knowledge and or sharing and discussing information with others, join the diverse online community for systems thinkers at Systems Innovation.

P.S. – Could We Survive a Dark Age Again?

While I was editing this post, I thought of a fiction I read in 2004. The book was Dies the Fire by S. M. Stirling, and it wasn’t a bestseller. A colleague of mine at IBM recommended it to me, and so I picked it up.

It is a post-apocalyptic saga set in America when an electrical storm produced a blinding white flash that rendered all things that require electronic power (including batteries) and fuels unusable. All modern conveniences were gone instantly, and all modern systems and facilities ceased to function, including banks, stores and prisons etc. Having money in the bank means nothing. We were back in the dark ages. The story is about the survival of two separate groups of people, alternating between two themes, technology and myth.

I never thought much about the story. However, reviewing this blog series while living through a pandemic and a technological Renaissance made me wonder if we could survive such an apocalypse with our “recipe execution” brain. Ciao!

Beautiful post. I love how you tackle the complex topic of complexity through a simple analogy and story telling. You have an art for writing. I will check out as many references as I can. In fact, in a different context I came across the “Livewired” book as well – which I’ll definitely get and read.

Thanks Joanne!

Hi Raj,

Thank you for your kind words. Complexity has fascinated me for a long time. Interestingly, AI and machine learning are playing a role in helping us better understand complex systems that will help us better understand the overall ecosystem including ourselves.

Warm regards,

Joanne

Thank you, Joanne for the wonderful way of putting it. It seems like the complexity of thought often overruns the perspective of the system. There is an approach that helps us go simply deeper: dispense with the words. Instead, draw the pictures.

Words help us fully describe the space we currently occupy, but create an epistemic bubble – a wall beyond which we can sort of “see”, but for which we have no nouns. Imagine the first hunters thinking of the spear, only without any word for spearhead, sharp, pierce, handle, length, attach, glue, tendon, or any of the other nouns that are important to spear technology. However, a simple drawing of a spear in a hand, and another in the side of a buffalo, got it across clearly. Nouns came much later.

Recipes are the means by which we transmit very specific and very limited techniques to the hands of the inexperienced. It is a form of remote control. We guide the person executing the recipe through the steps. This is good, but produces a co-dependency like relationship. We can be pretty successful by following recipes. We become dependent on them. Then we come to the place where we can’t execute without them.

The idea of the recipe was not to stop at execution, but to impart understanding. By making bread we become intimately familiar with how yeast works and how grain protein unfolds. Eventually we can make bread without a recipe. By blooming spices in water or oil and creating successful combinations, we learn how flavors work together to produce a symphonic signal of pleasure in both nose and mouth. No recipe will ever teach that.

We need the simplicity of playing with the dough and the humor of tasting our success and failure. It gets us past recipe and into the fun of cooking.

Have you read Henry Petroski’s “To Engineer is Human”?

https://www.amazon.com/Engineer-Human-Failure-Successful-Design/dp/0679734163

Hi Michael,

Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts. I always view comments as the extension of the post. We do need, more than ever, “the simplicity of playing with the dough and the humor of tasting our success and failure. It gets us past recipe and into the fun of cooking.”

I have not read “To Engineer is Human”. I just checked it out and will read it. Thank you!

Warm regards,

Joanne

Interesting. When I cook, either I already have an experience-based idea of what I want to do even if it is a new dish, or I look at 5-10 different recipes and in my head make a qualitative and selective synthesis (based upon my own tastes) that I do not write down and then just “execute”. The next time, the “recipe” may be slightly different (different vegetables, different spices, somewhat different proportions) but it is not “executed” with reference to specific quantities of specific ingredients, but more often “ratios” than can be adjusted or vary from one production to the next.

Concerning your comments about the brain, it seems likely that you (and/or your husband) would find the ideas of Gerald L. Edelman to be of interest.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmyfQY4TaVc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DX8q3Gv2_-I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_Edelman#Theory_of_consciousness

https://www.pnas.org/content/100/9/5520

Hi Robert,

Thank you for sharing your thought process when cooking, a nice improvisation. I have been interested in psychology and neuroscience for more than half a lifetime. Fortunately, there are many books that are suited for a layperson like me. No, I have not read or watched Gerald L. Edelman. Thank you for the links. I will certainly check them out.

Warm regards,

Joanne

A good thoughtful and well written article that gives a good account of something fundamentally important.

John

Thank you! John.

I’m happy to see that the message resonates with you and others. The reason I find complexity science fascinating is that it highlights our blind spots and therefore allows us to reflect and make better decisions for the future.

Warm regards,

Joanne

Great summary Joanne – I enjoyed reading it.

Often when humans are faced with tough decisions we seek to substitute a tough decision for an easier one: psychologists have named this the substitution effect.

I think that there are some parallels between complexity thinking and the substitution effect when it comes to learning about how our brains work.

I hope you are doing well 🙂

Hi Chris,

Thank you for reading my blog post! I’m doing well. Hope you are too.

I’m glad that you brought up the substitution effect from psychology. I read Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast and Slow” a few years ago. He says, “When faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.” I thought about the two systems, system-1 and system-2, that Kahneman described in his book while writing this blog post.

However, I see a chicken-and-egg issue between the “substitution effect” and the overuse of our left hemisphere over the course of industrialization. My argument is not that one of them is wrong. The key is “balance”. I decided to argue from a neuroscience perspective instead of a psychology perspective.

These topics are fascinating. I may write another post from a psychological standpoint when I have time.

I must add that as a layperson, my understanding is quite limited and therefore biased in my own ways.

Warm regards,

Joanne

This is really DEEP Storytelling is wonderful!

How we wish our “human world” was so simple – like our animal buddies

Thank you, Srinivaas. Our animal buddies are actually quite complex and have more collective intelligence than us humans.