It is a no-brainer that not all problems are created equal. But it is not a no-brainer that we’ve been solving all problems using the same way of thinking and the same method of inquiry regardless. As a result, our conventional approaches to problems often get in the way of dealing with the very problems we try to solve.

In this blog post, I explore two categories of problems from the perspective of complex systems. One is the problems of the parts or inherent problems. The other is the problems of the wholes or emergent problems. I also explore why emergent problems are wicked and what makes them wicked.

The Yellowstone Crisis and the Wolf Experiment

Shortly after I resigned from my corporate job in 2014 to research complexity science and systems thinking, I came across a short video, How Wolves Change Rivers (4.5 minutes). It is about how wolves ‘accidentally’ or unexpectedly changed the ecosystem in America’s Yellowstone National Park. By now the video has been watched online about 50 million times and the story reported across the world. Although the phenomenon is still debated by scientists, that is not the point of this post.

Wolves were eradicated in Yellowstone from 1872 to 1926. During the next 70 years when wolves were absent, the overall condition of the park declined drastically, including elk overpopulation, land erosion and plants dying off etc. The causes of the deterioration and degradation were not connected to the wolves’ absence. Efforts to improve the park’s condition focused on single, isolated interventions such as controlling the elk population by trapping and moving the elk or strengthening riverbanks. However, the park continued to decline.

Meanwhile, in 1967, the gray wolf species was listed as endangered in Yellowstone and its surrounding areas. After many studies, assessments and legal battles, a decision was made in 1994 to restore the wolf species by reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone as an experiment (History of Wolves in Yellowstone). In January 1995, 14 gray wolves from Alberta, Canada were introduced to Yellowstone and 17 were introduced in January 1996 (1995 Reintroduction of Wolves in Yellowstone).

The wolf experiment not only restored the wolf species but also rejuvenated Yellowstone’s deteriorating and degrading ecosystem as a result. The wolves’ positive impacts on the park baffle scientists to this day. According to Doug Smith, a wildlife biologist in charge of the Yellowstone Wolf Project, the still-unfolding trophic cascade is continuously being observed 25 years after and will take decades more research to fully understand.

I was awestruck immediately by the ecological phenomenon, the trophic cascade. I was equally shocked at how little we know about ecological systems or the ecological reality. After all, scientists have figured out the age of planet earth and mapped the evolution of the sapiens, geologists can date rocks and fossils back to billions of years, humans landed on the moon more than four decades ago, and we have mapped out 92% of the human genome with 99.99% accuracy… but we somehow had no idea how species interact and survive in the outside world, outside of our minds.

At the time, I was deep into Russell L. Ackoff’s work in interactive design and problem-solving. So, my mind gravitated towards problem framing and formulation, “what problems were the Yellowstone problems” or “how might we have framed and formulated the Yellowstone problems differently?”

In hindsight, we could see that the problems Yellowstone faced over the 70 years were not isolated problems of the individual species or of the landscape. The absence of the apex predator, wolves, resulted in a host of intertwined problems which emerged over time. We just started understanding the nature of these types of problems.

Inherent Problems vs. Emergent Problems

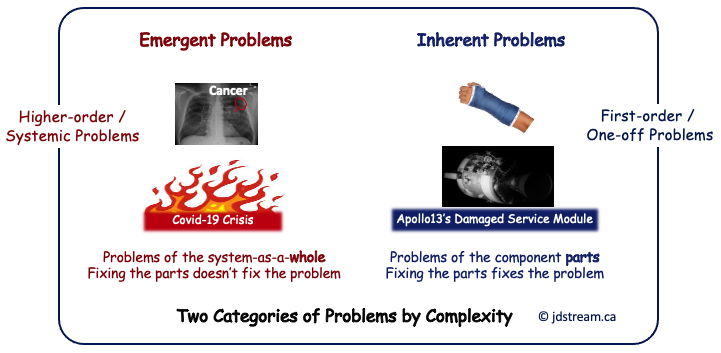

It turns out that there are two categories of problems, namely, inherent problems and emergent problems, as illustrated by the figure below.

Inherent problems are the problems of the component parts of a system. Fixing the broken parts fixes the problem. These problems can be clearly defined in terms of the component parts and how the system-as-a-whole is supposed to work. The causes of the problems can be traced and identified logically.

For example, a broken wrist is an inherent problem of the human body, and a flat tire is an inherent problem of a car. Some inherent problems are much more complicated but can still be diagnosed logically by taking the system apart, examining the parts, and finding the causal factors.

The problem that Apollo 13 encountered was a complicated problem but an inherent one. In Apollo 13, an explosion caused the oxygen tanks of the service module to vent. Given the circumstances, the only solution was to connect the service module to the lunar module so that the astronauts could return to earth. NASA’s engineers on the ground designed a workaround in record time using limited items on board including hoses from spacesuits, tube socks, and duct tape. The solution involved, literally, fitting a square peg into a round hole. Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 13 mission that never made it to the moon. NASA calls the mission a “successful failure”.

I love stories like this where humans triumph over adversity. The now-famous phrase commander Jim Lovell uttered, “Ah, Houston, we’ve had a problem”, has become a testimony to our abilities to solve difficult problems under life and death circumstances. However, most problems we face collectively today are difficult to an order of magnitude beyond our current level of understanding. These problems are emergent and wicked.

Emergent problems are a different beast altogether. They are not problems of the component parts of a system. They are the problems of the system-as-a-whole. Although one or more parts may be broken in the system, they are usually the symptoms or manifestations of an underlying problem, not the causes. Fixing the broken parts doesn’t necessarily fix the problem. In fact, it often gets in the way of dealing with the real problem.

In the case of the Yellowstone crisis, scientists didn’t fully understand that wolves were an integral part of the ecosystem and its absence wreaked havoc on the entire system. The problem metastasized to and manifested in both the animal species and plant species as well as in landscapes.

Examples of emergent problems are everywhere in our lives. For example, autoimmune diseases, an umbrella category of diseases where the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own parts. In the case of celiac disease, the immune system attacks the small intestine when one eats food containing gluten found in wheat, barley and rye. Over time, this immune reaction damages the small intestine and prevents it from absorbing nutrients which can lead to serious and fatal complications.

Is the small intestine the cause of celiac or a manifestation? We don’t know. Science points the finger at the immune system. I am, however, not so sure. As an autoimmune disorder sufferer, I find the notion a bit arrogant or ignorant. What if the immune system knows what it is doing and is doing the right thing? There are more than 80 types of autoimmune diseases affecting a wide range of body parts. There are no cures for most of them. If we stop seeing the immune system as the problem, we may broaden our viewpoints and start understanding how the human body works in alignment with the rest of the universe.

Other examples of emergent problems include cancer, the COVID-19 crisis, the opioid crisis, financial crises, poverty, inequality and all kinds of social-cultural and public policy problems. Many organizational issues are also emergent, although complicated by technology and rigid processes which make them complexicated.

(I can’t say that the word, “complexicated”, is my invention. It has been used as a Twitter hashtag since 2011. Hip hop artist Braille has a song titled “Complexicated” (2010) that starts with “simple message is so clear it’s complex…”. Milan Guenther responded to my LinkedIn post on complex systems with a question: “…What if a complex system includes complicated engineered components, that cannot be described by a few simple behaviours? I’m thinking of enterprises of course. Is the resulting system still complex, or will it become complexicated?”)

Emergent problems arise or emerge through the interactions of the parts, thus the name “emergent”. They are also known as complex problems or wicked problems. I prefer “emergent” because it makes explicit the emergent nature of the problems as well as the complexity of the underlying systems.

The term “wicked problem” was coined by Horst W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber in their 1973 paper, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. In the paper, they challenged the scientific approaches to planning and public policymaking and examined why they failed. Although the paper was written in the context of urban planning and social policymaking before complexity science existed, it continues to shed much-needed light on dealing with the challenges and crises we face today.

What Makes Emergent Problems Wicked?

Emergent problems are wicked not because they are innately elusive. They are wicked because they don’t fit our dominant way of thinking and rational methods of inquiry. As Jamshid Gharajedaghi, a collaborator of Russell Ackoff put it: “Chaos and complexity are not characteristics of our new reality; they are features of our perceptions and understanding. We see the world as increasingly more complex and chaotic because we use inadequate concepts to explain it.” (Systems Thinking: Manage Chaos and Complexity, Third Edition, 2009, p25). To learn more, check out my blog post on thinking.

The following three characteristics demonstrate why emergent/complex problems are wicked.

1. “There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem” (Rittel & Webber, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning)

Rittel and Webber pointed out that we couldn’t formulate wicked problems in the same way that we formulate inherent/tame problems.

How a problem is formulated or framed often determines the kinds of options available to address the problem. Every specification of a problem is a specification of the direction in which a treatment is considered. For example, when a problem is defined as “the overgrowth of the elk population”, interventions tend to be about controlling the elk population. When a problem is defined as “an overactive immune system”, treatments tend to centre around suppressing the immune system, and not surprisingly, that’s how we treat most autoimmune diseases today.

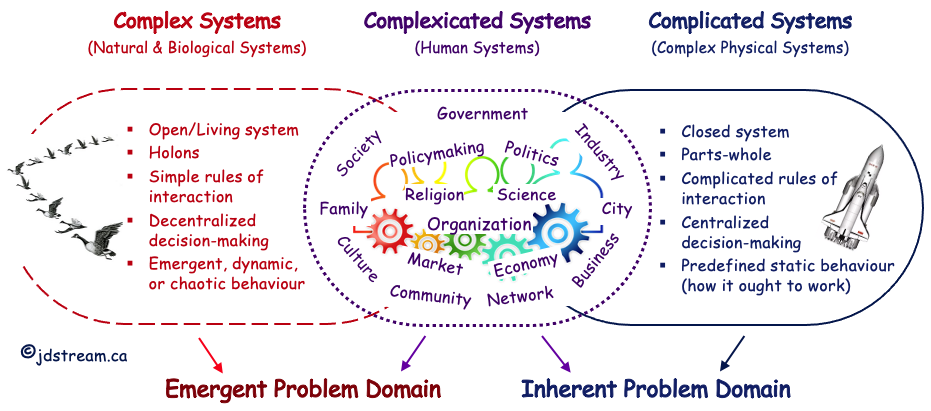

Defining the problem has long been an integral part of formulating a solution. It works for inherent problems but not for emergent problems. This is because the underlying systems are different. Inherent problems reside in complicated systems and emergent problems reside in complex systems. The figure below illustrates the differences between complex systems and complicated systems as well as the hybrid complexicated systems in between.

A complicated system has predefined conditions for how the system ought to work (predefined behaviour). When the system encounters a problem, root cause analysis involves identifying the differences between the system’s as-is conditions (actual outcome) and ought-to-be conditions (expected outcome). As soon as we trace the problem to some root sources, we’ve formulated a solution.

But this method of inquiry is unreliable for emergent problems where the underlying system’s ought-to-be conditions (expected conditions) are random and unpredictable. Besides, the perceived as-is or actual conditions also tend to shift and change. For emergent problems, problem framing and solution formulation become intertwined. Sometimes it is indistinguishable between a problem statement and a solution proposal.

Russell Ackoff told a story that he experienced in the early ’90s. (I apologize for not remembering the source of the story. If you know the source, please let me know. Thank you! — P.S. Goran Matic from Chaordic Design has kindly provided the source of the story (link here) in a comment below. Thank you, Goran.)

Ackoff was working with a group of academics in a small urban centre in Philadelphia to help the leaders of the community with development plans. One day, they were having a meeting when a piece of news broke. An 83-year-old local lady who had done remarkable work in the community had just died. She was returning home on the 4th floor and had a heart attack on the 3rd flight of stairs.

In the discussion that followed, the professor of community medicine spoke first: “We don’t have enough doctors. If we had more doctors, we’d be able to make house calls, and this might have been prevented”. The economist said: “There are plenty of doctors. The trouble is they are private practitioners, and she couldn’t afford one.” The professor of architecture asked: “Why don’t we have elevators in the building?” The professor of social works sighed: “None of you know anything about the lady. She was married and had a son who is a successful lawyer. If she wasn’t alienated from her son…” And it went on.

The story illustrates the difficulty in framing and formulating an emergent problem using our conventional root cause analysis. Experts often leap into first-order analysis through the lenses of their specialties. Besides, multiple perspectives don’t necessarily include or lead to higher-order perspectives. Sometimes we don’t even have all the relevant perspectives.

Taking COVID-19 as an example. Although it was declared as a public health crisis, the problem was framed mostly as a medical problem instead of a public health problem as evidenced by the narratives and the interventions from most countries. I will dive deeper into this in my upcoming blog post, Hidden Pathways Underlying Emergent, Wicked Problems.

2. An emergent problem often manifests in many parts of the system

An emergent problem usually arises over time. It tends to manifest in different parts of the system and creates a host of problems. Once metastasized, any single problem can be both the cause and the symptom of other problems like cancer. By the time the emergent situation catches our attention, it is often difficult to tell the causes from the symptoms of a multitude of entangled problems.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a hell of an emergent problem that has manifested in many different ways, forms and systems. At the centre of the battleground, we have the immune system and the virus, both complex systems entangled in other complex systems such as our personal health and wellbeing, the societies we live in, the socio-economic conditions we are under, the political systems governing us, the culture believes we hold, and the types of healthcare systems we have access to. We are intervening in all of these systems simultaneously without knowing how each system may be impacted in the process in the long run.

More than a year later, we are still in an arms race with the virus, itself a complex agent that can replicate/mutate to evade our immune systems and spread further into the world. The manifestation is still unfolding.

3. Every intervention to an emergent problem is a real-time experiment

Due to the unpredictable nature of emergent problems, every intervention is a real-time experiment and cannot be reversed. It is like putting a drop of blue ink in a glass of water. The blue ink will disperse into the water and can’t be extracted back out. We must bear the consequences, intended and unintended, resulting from interventions. One thing we can do is to take learning and feedback from the experiments seriously.

In the Yellowstone wolf experiment, scientists examined five alternatives for restoring the endangered wolf species. The first alternative, reintroducing experimental gray wolves, was recommended and adopted. The cascade effects of the experiment on the Yellowstone ecosystem as a whole, so far perceived as positive, are still being observed closely.

In the case of the COVID-19 crisis, the urgency of the problem didn’t allow us to conduct studies and assessments. We needed to act quickly. However, it doesn’t change the fact that interventions are experimental and irreversible.

That’s it for now.

P.S. – Nature is neither Harmonic nor Balanced, and … the Yellowstone Wolves

I still remember watching the documentary series, Animal World, on my parents’ tiny black-white TV in the ’80s in China. It was one of the two foreign TV programs from the U.S. The other one was Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse, which I watched too. I didn’t watch Animal World because I loved animals or the show. I watched it because there was only one channel.

My memory of the wild animal world from the show was not one of peace and harmony like domestic pets or zoos. Instead, it was tense, brutal, cruel and bloody at times which always made me squeamish and had me covering my eyes.

An ecological system is rarely static and harmonious. It is rather dynamic, full of chaos and unpredictability, and constantly changing. The theory that ecological systems are usually balanced in a stable equilibrium has long been discredited by ecologists, but the myth remains in popular culture and movies (John Kricher, The Balance of Nature: Ecology’s Enduring Myth, 2009, or this article from the National Geographic, July 2019).

The dynamic, chaotic and unpredictable nature makes complex systems difficult for us humans to decipher, and all the more intriguing.

By the way, if you are interested in the very wolves released in the Yellowstone National Park, you may want to check out Nate Blakeslee’s book, The Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West (2017). It is a beautifully written book about animal and human nature, about bonds, love, values, life and survival. I read the book a few years ago and wouldn’t mind reading it again.

Ciao!

Thank you for an informative and insightful read.

Thank you for reading it. Dr. Tracey Leghorn.

We still try and fix schools by treating the curriculum, teachers, leadership, and pedagogy or finances as problematic. My work on transformative learning and autopoiesis suggests the real problem is systemic and related almost entirely to same age organisation and the system it levers….the traditional school!!

Change the relationships liberated agency and managers….simple complex adaptive theory meets systems thinking.

Thank you for responding to my post, Peter.

Your work in transformative learning and autopoiesis sounds very interesting. Schools and institutions are the very places where systems thinking and complexity science are desperately needed. I’m curious how one may apply complexity thinking in learning.

Just checked out your website, “One school at a time and a thousand lives made better”, well said.

All problems are created from solutions

Thanks Joanne,

I’m using as a definition of a problem: a difference between an actual and the expected situation with negative emotional charges. (A situation with positive emotional charge just means you’ll reach your problem faster). From this definition you can see we will have problems in solving problems.

Firstly because of people have emotions around a situation. They should be addressed first. (Emotions have right of way, we say here). I tend to emotions by participants associated with the (perceived) situation. Because most of the time they “know” we don’t have solutions.

Secondly because expectations people have of the situation. People have all kind of assumptions, wishes, intentions, even goals. I tend to lower my expectations.

And thirdly difference in perceiving what the actual situation actually consists of. In this last case, we have also to take into account the cultural context in which the actual situation is being framed. So every problem comes with its own problems. (I will address this in the forth coming workshop on Creating Paths of Change).

As in your example by Ackoff shows, different people experience an actual situation differently, will have different expectations and differ in their emotional response. These differences are not attributes of the problem, but projected on the situation and its “solution”.

—

I apply systems thinking this way: my problems are symptoms of your (plural) solutions and your solutions will cause symptoms of our problems.

Also in his book The 5th discipline Peter Senge shows how helping people solving their problems may lead to an undesired situation in which the helping person becomes addicted too helping. So I also apply system thinking in preventing other people from becoming dependent on me in solving their problems.

Leadership – I’ve learned -, also implies learning people to be able to solve their problems themselves.

This in my opinion is the difference between a consultant and a facilitator. A consultant needs acceptance of his or her solution. Facilitator guide a system in finding it’s own solutions. I tend to call these “resolutions”.

—

A wicked problem – in my view – is a situation in which I ask myself, “Am I solving problems because I’m having solutions, or do I have solutions because I’m solving problems?”. So problems solving is inherently paradoxical.

I don’t make distinctions between “problems” and “solutions”. Because living (or life) is not a problem I can fix.

A few weeks ago, a client said to me “… but the civilians demand solutions from me!”. I asked him : “… and (I never use ‘but’) who are you, when they ask for solutions from you?”. After some thinking, he concluded that he expected them to ask him for solutions. So he induced his own “wicked problem”.

By expecting expectations of solving problems, you may also create problems. “I cannot solve problems,” I used to say, “I can only enlighten, lighten the burden”.

—

As I said, problem solving is inherently paradoxical: a problems’ problem. Regarding your “inherent” and “emergent” problem domains: we’ve got also two types of paradoxes: part-part paradoxes and whole-whole paradoxes.

In the first case, the parts of the group or system are complementary. Parts make up the system-as-a-whole, which is an individual. They’re what we call “organized”, “more than the sum of its parts”. The parts belong together, work together, like a machine. A part of the system can manage or control the system, possessing a “model” of the system.

A faulty part, hampers the whole. Because we can predict expected outcomes, we can solve these types of problems. The problem can be “solved” by analyzing and testing from the perspective of the whole: repair, change a part. This is the “inherent problem domain”. We pay by creating whole-whole paradoxes.

The latter case, the parts are wholes, they are “the same”, “holons”. The whole can be divided in the same parts. Interactions are complex and cannot be reduced to analysis. We can call these “organisms”. “Whole – whole” systems don’t have a hierarchy and their using “decentralized” decision making . What’s even worse, these systems don’t mind an individual. They can be replaced.

Natural and biological systems don’t have problems with themselves. The individual – being part-part systems – may have them, but the whole-whole “dividual”, doesn’t.

Only human beings, by attributing expected behaviour on a “system”, create problems. Off course, as in you picture, human beings live in both systems at the same time.

—

We’re individuals taking part in groups (I love a “parts party”). We’re part of machines we’re calling organizations.

The Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam has been called the largest machine in The Netherlands. We’re also organisms, individuals in our own right. The Netherlands is one of the most densely populated organisms (emergent problems domain) in the world.

The sticky (tricky) problem is that we can solve problems in airports, but we cannot solve problems with people travelling: climate change.

—

The concept – idea, fiction – of systems and thinking systematically can be very useful in solving some inherent problems. Problems remain constructs of the human ingenuity. They don’t really exist in any natural domain. Nature doesn’t care about us.

We can only strive for resolving, absolving, finding elixirs (a potion, solution, not for an individual, but for the community) that people themselves explore (like in the Hero’s Journey). Solving problems is about goals, destinations, not about speed, of the directions we take. Problems disappear where headings appear.

Hi Jan,

Thank you so much for taking the time to share your insights and wisdom as always!

Your ability to explain concepts using simple and yet powerful words such as “actual” vs. “expected” vs. “perceived” situation/outcome is admirable. I have stolen those words and added them to the post which clarified the meaning of the descriptions. I hope that you don’t mind.

To your comment on The 5th Discipline, “Peter Senge shows how helping people solving their problems may lead to an undesired situation in which the helping person becomes addicted too helping. So I also apply system thinking in preventing other people from becoming dependent on me in solving their problems” – So true! I will re-read the book.

“By expecting expectations of solving problems, you may also create problems” – this should be a principle! Problem-solving is indeed inherently paradoxical.

Your take on leadership, “leading people to be able to solve their problems themselves”, and on the difference between a consultant and a facilitator, “a consultant needs acceptance of his or her solution, a facilitator guides a system in finding its own solutions”, are the best I have seen.

I like your analogy between inherent-vs-emergent problems and airport-vs-travelling. “The sticky (tricky) problem is that we can solve problems in airports, but we cannot solve problems with people travelling: climate change.” My question to you: can we “dissolve” the climate change problem as Ackoff had suggested for “messy” problems?

Thank you again! I look forward to next week’s workshop “Creating Paths to Change” with you!

Sincerely,

Joanne

Great article – thank you!..

By the way, I was also lucky to come across that Ackoff story, which I presented at a conference paper – and everyone loved it, because it’s so evocative; except that I had also lost the source.

I just found it, and it’s apparently entitled: “Disciplines, the two cultures, and the scianities” (Ackoff, 1999).

It can be accessed on ProQuest, here: https://www.proquest.com/docview/196891149

Hope that helps everyone enjoy it even more!

Hi Goran,

Thank you very much for reading my blog post and for sharing the source of the Ackoff story! I would like to update the post to include the source information and attribute it back to you if you would provide your contact information (website or LinkedIn or Twitter etc).

Kind regards,

Joanne